Following the noteworthy Democratic successes in the 2017 elections, we’re once again hearing that Democrats can achieve their electoral goals without any greater success among the white working class. Indeed, some on the left seem to feel that Democratic gestures toward the white working class would not only be ineffective but are politically suspect.

“There’s always been something problematic about the Democratic Party’s fixation on white working-class voters,” writes Sally Kohn at the Daily Beast. “After Alabama, it’s clear that obsession isn’t just fraught with bias. It’s also dumb.”

Steve Phillips of Democracy in Color remarked in a New York Times op-ed: “The country is under conservative assault because Democrats mistakenly sought support from conservative white working-class voters susceptible to racially charged appeals. Replicating that strategy would be another catastrophic blunder.”

“The ceiling with the white working class is what it is,” Phillips adds with a shrug in The Nation.

However popular, the view that Democrats can get along without working-class white voters is simply wrong. It reflects wishful thinking and a rigid set of political priors — namely, that Democrats’ political problems always stem from insufficient motivation of base voters — more than a cold, hard look at what the electoral and demographic data say. Consider the following:

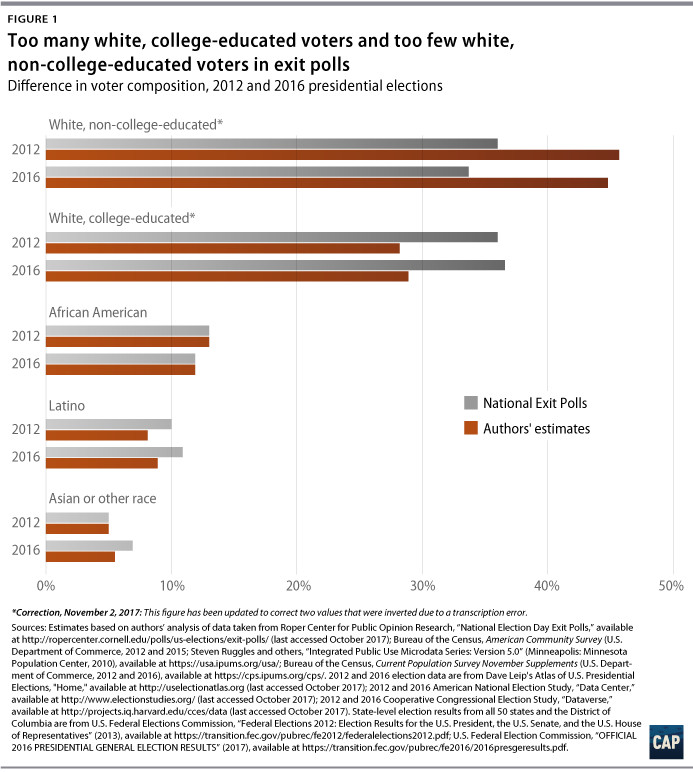

There were far more white non-college voters in the 2016 election than shown by the exit polls

The exit polls claimed there were more white college voters (37 percent) than white non-college voters (34 percent). But in a report for the Center for American Progress synthesizing available public survey data, census data, and actual election returns, Robert Griffin, John Halpin, and I found that 2016 voters were 44 percent white non-college and just 30 percent white college-educated. (The balance were black, Latino, Asian, or “other.”)

This suggests the exit polls were not just wrong but massively wrong, especially in the context of Rust Belt swing states, where errors were even larger and the political implications of misunderstanding graver. (This is a longstanding problem that is probably intrinsic to the exit poll methodology of public interviewing, which favors educated respondents. Among other reasons, educated voters may be more willing to take a survey in a public place, and so wind up being overrepresented.)

Simulations we conducted indicated that Hillary Clinton would have won the 2016 election if she had held Obama’s modest support among white non-college voters from 2012

In 2012, Obama lost whites without a college degree nationally by 25 points. Four years later, Clinton did 6 points worse, losing these voters by 31 points, with shifts against her in Rust Belt states generally double or more the national average.

Had Clinton hit the thresholds of support within this group that Obama did, she would have carried, with robust margins, the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Iowa, as well as (with narrower margins) Florida and Ohio. In fact, if Clinton could simply have reduced the shift toward Donald Trump among these voters by one–quarter, she would have won.

To put this into fuller context: If Clinton had replicated the black turnout levels enjoyed by Obama in 2012, she still would have lost the 2016 election, because the other shifts against her were so powerful.

In Arizona, Georgia, and Texas, where Clinton actually improved on Obama’s performance in 2012, she did better among not just white college voters but also white non-college voters

Improvement in support among members of minority groups had very little to do with improved Democratic performance in the presidential race in these states in 2016. This suggests that if Democrats hope to carry these states anytime soon, they will need not just to mobilize the minority vote (which is, indeed, burgeoning) but also hold and expand their support among whites. And that most certainly includes those states’ very large white non-college populations.

Doug Jones would not have won the Senate election in Alabama without a substantial shift toward him among white non-college voters

The Daily Beast’s Kohn and others argue that heavy black turnout and support led to Jones’s victory — period. But Jones’s triumph was not attributable to his strong showing among black voters alone, or even a combination of black voters and white college graduates. My analysis indicates that Jones benefited from a margin swing of more than 30 points among white non-college voters, relative to the 2016 presidential race in the state.

The swing toward Jones was for sure even larger among white college graduates. But without the hefty swing among the white non-college population, particularly women, there is no way Jones would have won the state, or even come close.

The white working-class vote is still Democrats’ critical weakness

Despite Democratic gains in Virginia, Gov. Ralph Northam still lost the white non-college vote by more than 30 points; that’s little better (if at all) than Clinton’s performance in the state in 2016. This is especially worrisome because white non-college voters remain a larger group than white college voters in almost all states — and are far larger in the Rust Belt states that gave the Democrats so much trouble in 2016: Iowa is 62 percent white non-college versus 31 percent white college; Michigan is 54 percent white non-college versus 28 percent white college; Ohio splits 55 percent to 29 percent; Pennsylvania 51 percent to 31 percent; and Wisconsin 58 percent to 32 percent.

Ohio, where Democrats’ white non-college deficit roughly doubled from 16 to 31 points in 2016, is a good example of the challenges Democrats face. Given this deficit, Democrats could completely replicate, in 2020, Obama’s high-water performance among black voters and still lose the state handily, probably by around 5 points. There is no way around it — if Democrats hope to be competitive in Ohio and similar states in 2020, they must do the hard thing: find a way to reach hearts and minds among white non-college voters.

This is hardly an impossible task. The view that white non-college voters who do not already vote for Democrats are hopelessly racist and reactionary is a canard. They’re a vast and variegated group.

Indeed, there are positive signs already in trends among white non-college voters, particularly among millennials (Democrats actually carried this group in many states in 2016, according to our analysis), and to a lesser extent among women (Democratic margins in this group of women, while negative, tend to run 20 points better than among men.) To build on these trends, Democrats will probably have to offer something besides vigorous denunciations of Trump, who is more popular with these voters than with the rest of country (though he’s slipping).

That does not mean that Democrats need to capitulate to Trumpism by, for instance, changing their position on key immigration issues like DACA. That would hardly pull Trump’s hardcore supporters from their man, and it would compromise a serious policy commitment of the party. Instead, Democrats should reach out to those white non-college voters for whom issues besides immigration are potentially more salient.

It is on economic issues that these voters are most open to overtures, the polling data shows. Indeed, if Wall Street financier Robert Rubin, the Democrats’ quintessential 1990s neoliberal economic figure, is now advocating for a massive public jobs program, perhaps it’s time for Democratic politicians to make a bold economic offer along those lines. Such a program could be linked to investment in desperately needed infrastructure, including not just roads and bridges but also community-anchoring institutions like schools and child care centers.

The scale of such a program would eclipse the Democrats’ current weak-tea “A Better Deal” approach; it would be a signature offering, as opposed to a laundry list of proposals. And it is well-documented that infrastructure and community investments are popular across the lines of party and class.

This may not be exactly the right program or the most effective way to frame it. But putting something in play that aggressively attacks these voters’ problems makes more sense than standing pat and hoping against hope you can succeed while ignoring those oh-so-problematic working-class whites.

Ruy Teixeira’s latest book is The Optimistic Leftist: Why the 21st Century Will Be Better Than You Think. He is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.